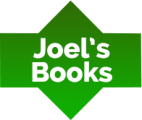

Dust In My Veins by Antuan Wilbon

Archibald Campbell, a slave owner, made a deal with a powerful Voodoo Priestess named Simbi to bind his slaves to him forever and grant him an unnaturally long life because he was afraid of losing his slaves and plantation.

In 1862, the United States was on the brink of change. Whispers of Abraham Lincoln’s proposed Emancipation Proclamation ran like wildfire through the streets, and there was little doubt that soon all the men and women that had once been subjugated and forced into slavery would finally be free. However, not everyone welcomed this change. Archibald Campbell, terrified of losing his slaves and plantation, made a deal with a powerful Voodoo Priestess named Simbi. She wove a spell that would bind his slaves to him forever and grant him an unnaturally long life.

For centuries, Archibald and his slaves lived in isolation in Derniere, a town hidden in a forest. The slaves longed to escape, and over time, many managed to do so. Archibald discovered that with each escaped slave, he aged while his slaves turned to dust. To prevent the curse from ending his life, he had to keep a member of each slave’s bloodline in Derniere. In present-day Chicago, Jaxson faces a difficult homicide case and is put on temporary leave after a near-death experience. He receives a letter awarding him property in Derniere, where he meets Angela Allen, a professor searching for answers about the town. Together, they uncover its secrets and work to unravel its mysteries.

Excerpt from Dust In My Veins © Copyright 2023 Antuan Wilbon

CHAPTER ONE

NEW ORLEANS, 1862

In time, the streets would rage with fire and blood.

Soldiers and slaves would take up arms against one another, and the sky would darken with bullets and smoke and gunpowder. It was the way of things; he was certain. With every day that passed, the negroes’ voices grew louder and louder. They could sense a revolution, could smell the winds of change in the air. Anger filled the hollow spaces of the city, flooded the streets in a way it never had before. And Archibald knew that soon that anger would spill over, and with it there would be blood.

Archibald stared at the dais before him and watched as the familiar red and blue of the confederate flag was pulled down, ripped from the pole and torn in two.

There were shouts around him, the sounds of rage and revolt, yet they were hardly more than a whisper against the rush of blood pounding in his ears. Inside his chest his heart beat a sombre melody, a slow reproach of inaction. He watched as they raised a new flag, one that once stood for everything he believed in. Now, he wasn’t sure what the stars and stripes stood for. Everything had changed overnight.

“We can’t let this happen,” Isaiah whispered next to him.

Archibald remained silent, watching as the American flag rose higher and higher up the pole. Its movement was a stilted staccato, altered only by the rustling wind. The flag flapped half-heartedly, as if to sigh, then became limp once more.

Seeing the flag hanging lifeless against its pole broke something inside of Archibald. It was bad enough, the changes that Lincoln wanted to impose. But the world seemed to be leaning in his favor, and that was something Archibald simply could not understand. He wondered if the world had gone mad, if all this talk of progress was nothing more than a fool’s wanton pandering. He wondered idly if there was perhaps some strategy to the move he could not see—surely there must be, else what would be the point?

Swallowing back the sour taste on his tongue, Archibald turned and headed back to his carriage. Isaiah followed closely behind, chewing his lip as he glanced back at the crowd. By the time they closed the carriage door behind them, a ripple that whispered of violence had already taken hold among those gathered.

“It won’t be long before the fighting starts,” Archibald murmured with a shake of his head. “Best we get back home.”

For a time, the pair sat in silence. Archibald nursed his morose mood, and with every bump and divot in the road his thoughts turned increasingly more black.

“What right does he have to take our slaves from us?” Isaiah said at last, indignation on his tongue.

“Abraham Lincoln?” Archibald asked, arching an eyebrow. “I should think holding the title of President has something to do with it.”

“Well, I don’t care if he is president,” Isaiah spat. “This proclamation of emancipation is utter nonsense. What is he playing at? Does he not see the absurdity?”

Archibald’s mouth tightened to a thin line. “He will. He must. Everyone knows that giving the negroes their freedom will invite insurrections across the nation. And who will they revolt against when the time comes?”

“Certainly not Lincoln.” Isaiah scoffed.

“Certainly not. It will be men, simple men like you and me. Men that have worked hard to provide for this country, men that have fought on its behalf. We who have given everything in service of our country shall be the ones to pay the price.”

A hard knot of fury settled beneath his ribs. It lodged itself against his bones, grating with every breath he took until he burned with it. Was it not enough that he had given all of his life to his country? Must he now part with his slaves, too?

“I, for one, won’t stand for it,” Archibald hissed. “I will not have everything I’ve worked so hard for stripped from me. I will not give up my negroes. They are mine to do with as I please. And that is precisely how they will stay. Mark my words.”

***

The shadows of night pooled around him like inky curtains, draping themselves against his feet as Archibald sat nestled in the light of his lantern. He gazed absentmindedly at the acres of tobacco plants that stretched before him, the milky light of the moon lending an eerie pallor to their broad leaves. Often, he came to sit on the porch in the middle of the night, when his leg ached and his mind wandered, and the only thing that gave him any certainty at all was a fervent prayer. On those nights, the cool air would soothe him, and he would close his eyes and listen to the chirping of crickets and the wind sighing through the trees. His restlessness would fall away, daunted by the prospect of peace, and Archibald would return to bed eased of whatever burdens plagued him.

But tonight was different. There was no promise of peace, no whisper of wind. There was no soft kiss of starlight or chorus of crickets. The air was hot and still and heavy. It made his clothes cling to his skin, soaked through with his sweat, and as he sat there staring at the crops, he felt suffocated by it all. Hundreds of acres stared back at him, as if to mock him. Without his negroes, they would wither and rot and die. All of them. Every last one would become a useless thing, another hole in his pocket that he simply couldn’t afford.

And what of his wife? His children? What would their lives be without the negroes to keep them? A house of their standing was far too much work for his wife to maintain, and he dared not let his children wander the plantations alone.

He mused silently, the minutes ticking by in steady rhythm. The more he thought on it, the less plausible it seemed. Perhaps there were families that could part with their slaves and would hardly notice a difference, but that was not his family. If Lincoln passed his emancipation law, Archibald was all but certain he would be crippled.

My profession is online marketing and development (10+ years experience), check my latest mobile app called Upcoming or my Chrome extensions for ChatGPT. But my real passion is reading books both fiction and non-fiction. I have several favorite authors like James Redfield or Daniel Keyes. If I read a book I always want to find the best part of it, every book has its unique value.