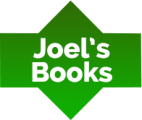

When Morning Comes by Arushi Raina

It’s 1976 in South Africa.

Written from the points-of-view of four young people living in Johannesburg and its black township, Soweto—Zanele, a black female student organizer, Meena, of South Asian background working at her father’s shop, Jack, an Oxford-bound white student, and Thabo, a teen gang-member or tsotsi—this book explores the roots of the Soweto Uprising and the edifice of Apartheid in a South Africa about to explode.

In the black township of Soweto, Zanele, who also works as a nightclub singer, is plotting against the apartheid government. The police can’t know. Her mother and sister can’t know. No one can know.

On the affluent white side of town, Jack Craven plans to spend the last days of his break before university burning miles on his beat up Mustang, and crashing other people’s parties.

Their chance meeting changes everything.

Already a chain of events are in motion; a failed plot, a murdered teacher, a powerful police agent with a vendetta, and a secret network of students across the township. The students will rise. And there will be violence when morning comes.

Introducing readers to a remarkable young literary talent, When Morning Comes offers an impeccably researched and vivid snapshot of South African society on the eve of the uprising that changed it forever.

AmazonExcerpt from When Morning Comes by Arushi Raina © Copyright 2024 Arushi Raina

PROLOGUE

Jack

I DREAM OF ZANELE AT THE WHEEL, HER KNUCKLES AND FACE OUTLINED BY STREETLIGHTS. WE SPEED PAST VACANT LOTS. SHE’S DRIVING TOO FAST. RAIN COMES thick and heavy on the windows. It’s the kind of storm that happens only on the highveld, the thunder loud and rapid. She doesn’t speak. I need her to. Maybe she’s counting the people who’ve died since we first met.

I calculate how fast the storm is coming up behind us—as if that helps. Zanele is taking us somewhere only she knows.

The things I am good at, lying and mathematics, are useless now. In the moments before the end, I can do nothing.

We crash onto the highway railing, the front chassis crumpling into the windscreen.

Another scandal, a black girl and a white boy found in a car with no explanation besides the obvious one.

THAT’S WHAT I DO NOW—SLEEP AND WAKE UP AND GO OVER THINGS THAT HAVE ALREADY HAPPENED OR MIGHT HAVE HAPPENED. I EAT BREAKFAST, A BOILED EGG and four slices of white bread, while I wait for a phone call that I know won’t come. In Soweto, smoke rises from the shacks. Meena says that ever since the protest the police fire at plastic bags, animals, little boys—anything that moves. I read the newspaper over and over, thinking they’ll mention Zanele. But they don’t. The same footage on the protests repeats on the television. I call Meena at the shop and she tells me no news is good news.

I ask for less and less as the days pass. First, I wanted Zanele to apologize for all the things she didn’t tell me, to apologize for disappearing without warning. Then all I wanted was for her to come back. Then it didn’t matter if I didn’t see her again. As long as she was alive.

ONE

Zanele

WE WERE GOING TO PUT DYNAMITE UNDER THE POWERLINE TOWERS. THERE WERE THREE OF US THAT DAY AT THE ORLANDO POWER STATION. BILLY, PHELELE AND me. It was after school, and we’d come to make sketches—sketches that would show where the dynamite needed to go.

The power station’s white caretaker explained how the electricity was generated and transported to the white areas of Joburg. As he talked he nodded and smiled, showing his dirty teeth. Billy nodded, flashing back his teeth, clean and white like an advertisement. Phelele and I looked at each other. The caretaker suspected nothing.

On the other side of the wire fence, children stared at us. They stood barefoot on long grass that had turned brown with the cold. Behind the fence and the children, the land dipped and rose. I could barely make out the road back to Soweto.

As we walked back, we saw rows and rows of corrugated roofs turned copper as the sun went down. And I imagined the Orlando power station exploding—the black bars of the towers flying apart and the lights going off in white people’s homes. For a moment, it would be a blackened white city. It would warn the mlungus of what we would do if they didn’t give us what we wanted.

IN HIS SHACK, BILLY MADE THE SKETCHES OF THE POWER STATION TO SEND TO THE UMKHONTO WE SIZWE IN MOZAMBIQUE. THEY HAD EXPLOSIVES. THEY WOULD slip back across the border and blow up the towers.

With a sharpened pencil, Phelele added arrows to the drawing to show where the dynamite should be placed.

They gave me the finished sketches. I had to drop them off at the train station. The envelope taped under the bench. I went alone, taking the path past the shebeen where Mankwe sang.

Before the power station, Billy, the meetings, I had just been Mankwe’s sister, the Mankwe with the magic voice.

Now I was the sister who helped plant explosives.

AFTER BILLY AND PHELELE WERE ARRESTED, I WAITED FOR THE POLICE TO COME FOR ME. BUT THEY DIDN’T. IN COURT A MONTH LATER, THEY AND TWO OTHERS I didn’t know were charged with terrorism. The court ruled that Billy had recruited boys to join military cells in Mozambique that were plotting to overthrow the government.

Now the four of them, chained, are walked out of the court with their arms cuffed behind them. The cuffs are in the space between the sleeves of Billy’s nice coat and his hands. I look away but I see the cuffs everywhere, metal glinting in the afternoon light.

Billy starts singing as he walks past us. Asibe saba thina. I reach out and the blue fibre of his coat gets caught in my nails. Then the policeman pushes him. Billy’s voice is low, soft, always the one the gogos in church liked best. We all join in with Billy, but Phelele is silent, head bowed. The policemen let us sing, because they don’t understand what the song means. Or they don’t care. They have Billy and Phelele. It doesn’t matter if we sing that we do not fear them.

As the van doors slam shut, Phelele’s eyes meet mine through the metal grating. This could be the last time I will see her. The policemen get inside the cab, red-faced and satisfied. The front doors close and the van pulls out. Everyone runs after it.

And I wonder who told the police about Billy and Phelele.

“Come, Zanele.” Vusi takes my shoulders, turning me away from the crowd. “Time to go home.”

We walk past a long, clean black car. A blond yellow-haired man sits in the back seat, watching us and smoking. In the front, a black driver and a white policeman. I can’t see their faces. Behind them, buildings form an outline of grey rectangles against the sky. Hillbrow Tower stands above the rest of the city. I’ve heard there’s an elevator that takes you to a restaurant at the top.

We were thinking of targeting that too.

LATER THAT NIGHT, I PUT ON LIPSTICK AND GLITTER, AND SLIP INTO MY SISTER’S SEQUINED DRESS. IT IS MY NIGHT TO SING AT THE SHEBEEN. AND I AM BACK TO being the person I used to be, before all of this happened.

Jack

OLIVER, RICKY AND I GRADUATED FROM JEPPE HIGH SCHOOL LAST DECEMBER AND STARTED CRASHING PARTIES SOON AFTER. WE DIDN’T HAVE ANYTHING BETTER to do. Oliver was at Tuks for engineering, Ricky was “taking some time off” and “thinking of studying in the States” and I was free till August, when I’d leave for Oxford.

So far, we’d been to dozens of them, including a cabinet minister’s birthday party and Miss South Africa’s charity gala.

I was always the one who talked our way in. People wanted to meet me. Oliver liked the planning, planned more than we needed. And Ricky came along because he liked to boast in a casual way about what we’d done, how we’d got away.

At the gala last weekend, we tried on tuxedos and bad American accents. We finished trays of champagne and skewered chicken because everyone there had been pretty boring. Miss South Africa even fawned over us for a few seconds, though Oliver was too nervous to say anything to her. Ricky thought she was average-looking. Later I went over to Megan’s and told her the whole thing had mostly been a waste of time.

I WAS HAVING DINNER IN THE GARDEN WITH MY PARENTS WHEN THE WHITE CARPULLED UP. THE POLICE STEPPED OUT AND I SAW MEGAN IN THE BACK. I ran forward to stop them from opening the door.

“I wish you wouldn’t let Megan call at this time,” my mother noticed after me. She didn’t like Megan, but everything she said to me these days was easy to ignore.

My profession is online marketing and development (10+ years experience), check my latest mobile app called Upcoming or my Chrome extensions for ChatGPT. But my real passion is reading books both fiction and non-fiction. I have several favorite authors like James Redfield or Daniel Keyes. If I read a book I always want to find the best part of it, every book has its unique value.