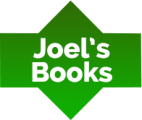

Concerning Fanaticism in The Human Race by Massimo Fantini

A debate on the human condition

Human Condition Trilogy Book 1

Elijah is a promising young lawyer, in love with his work and confident in the potential of the human race.

His law firm’s senior partner gives him his first important assignment. Elijah will have to follow the case of Leonard, an elderly engineer who lives in Montepastore, a small village in the Bolognese Apennines (Italy).

Leonard's question concerns the supplementary contribution that engineers enrolled in the professional register are required to pay to Inarcassa, the Engineers’ Pension Fund.

At first, the case seems simple. It was the subject of a previous ruling by the Court of Cassation. But Leonard is not satisfied with an institutional response. He wants to know why. He wants to know what hides behind the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Leonard's demands grow meeting after meeting, and the subject of the dispute widens to include ethical, religious, and historical concerns.

As in the previous manuscripts, questions about the human condition are at the center of this philosophical debate. In the absence of answers, what is the point of writing about anything else?

Amazon Author's Goodreads Page

Excerpt from Concerning Fanaticism in The Human Race© Copyright 2024 Massimo Fantini

Chapter 6

Elijah woke up numb from the cold. He got up and tested the temperature of the radiator by tapping it lightly. It was freezing. Then, he went to the kitchen to check the boiler. The alarm light reading ‘Insufficient Water Pressure’ was flashing. The young man turned on the water circuit’s supply tap. When the pressure reached 1.2 atmospheres, the burner started up.

Elijah made his way to the bedroom and then grabbed the doorhandle, turning it slowly. The door was no longer locked, so he went in and – in the dim light – saw Paola shivering under the covers.

The young man slipped into bed and hugged her tightly, massaging her arms to warm her up and kissing her neck. The girl let herself be cradled.

Suddenly, Paola put her mouth close to Elijah’s ear. “The credit is mine, not God’s,” she whispered. “Robbing our merits and attributing them to God invalidates free will. It makes everything predestined. It’s not like that. I have the right to decide whether to go to my parents for lunch or not. If I choose to go – if I make this sacrifice – the credit is mine. Clear?”

Elijah merely nodded. The girl’s reasoning seemed persuasive, but it erred on oversimplification. It was necessary to distinguish between liberty and free will. However, the young man decided not to linger in further discussions concerning articulated topics so early in the morning. It was too complex to explain. Elijah himself was still perplexed. He was certain that human actions were in some way guided by God’s will, but he had struggled to reconcile God’s design with humankind’s free will. On this dilemma, he had also confronted the priest of Saint Mary the Convinced’s church, who had convinced him to rely on faith, so that “everything would be all right.” Even in that case, Elijah simply nodded. However, if trusting in faith succeeded without difficulty, Elijah could not declare himself convinced, because there was always something jarring. When, during his youth, he had studied some theological and philosophical texts that delved into the theme of free will, he had found himself faced with a pile of colored tiles cut out in a variety of ways. They were the pieces of a large puzzle. Only by reassembling it, would he be able to construct a truly convincing thought. At the beginning, the work was dependent upon Augustine of Hippo’s texts and their systematic treatment on the subject. Thanks to him, Elijah had learned how freedom grants the ability to achieve one’s purposes, making humans potentially capable of getting what they want. On the other hand, free will was a specialized ability used to discern good from evil. The individual endowed with the ability of choosing good over evil – which grants them the chance of accessing salvation – is the only one who has been touched by divine grace. God determines a priori who can be saved and who cannot; only divine grace can instill the effective will to pursue the choice of good, a will that would otherwise be easy prey to evil temptations.

Thus, thanks to the help of Augustine of Hippo, some of the tiles started matching and the puzzle began to take shape. Sometime later, Elijah had read Paul of Tarsus’s Letter to the Romans, which reads: “For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do – this I keep on doing. [1]” From that moment on, the pieces of the puzzle never perfectly matched; where the outline agreed, the painting on the pieces did not, and vice versa. Elijah had then decided to give greater priority to organizing the tiles by the colors of the painting, in homage to God’s plan. He had grabbed a hammer, positioned the tiles according to these colors and struck repeatedly until all of them fit together, nearly perfect. That day, the young man had just returned home after carrying groceries his neighbor had ordered from the store to her kitchen. The old lady could no longer walk without her walker and Elijah helped her with errands. Applying the reasoning of Paul of Tarsus, Elijah’s desire to do good – but the inability to do it – had materialized in a bad deed. Was helping neighbors good or bad? In order to do good, should he have perhaps thrown her down the stairwell together with her walker? Furthermore, if individuals do not do the good they want, but the evil they do not want, would it not be better to give up doing anything at all? However, giving up entails the sin of sloth, and Elijah found himself at another dead end.

Supported by faith, the young man had continued hammering the tiles against each other anyway, until he was left with only the last tile and two holes to fill. The tile didn’t match either the painting or shape. Indeed, if only grace can suggest the way to good – and humans do not know whether they have received it or not – that means that they are unable to distinguish good from evil.

Elijah had identified two possible cases. If the individual were to receive grace, then the grace itself would show them the way to good, and they would not have to worry about discerning good from evil. If, on the other hand, the individual were devoid of grace, they would not be able to distinguish good from evil.

[1] Holy Bible, Letter to the Romans 7, 18-20

My profession is online marketing and development (10+ years experience), check my latest mobile app called Upcoming or my Chrome extensions for ChatGPT. But my real passion is reading books both fiction and non-fiction. I have several favorite authors like James Redfield or Daniel Keyes. If I read a book I always want to find the best part of it, every book has its unique value.